Palestine has a long and vast history. First documented in ancient Egyptian tablets as Peleset over 3000 years ago, the region between the Mediterranean and the river Jordan has come to mean many different things to many different peoples.

Throughout the ages, Palestine has been home to dozens of cultures, kingdoms and empires. From Assyrian and Nabataean, to Persian and Roman -and many more- each influencing as well as being influenced by the rich cultural and civilizational mélange that defined the area. These ancient influences can still be felt today in the idioms, vocabulary and toponymy used by its native Palestinian population. Even Palestinian agricultural practices can be traced back to the Natufians -one of the peoples credited with inventing agriculture- who called Palestine and the fertile crescent their home, as far back as 9,000 BCE.

Before we continue, it is important to stress that when we talk about Palestine, we are not talking about a Palestinian nation state. For the vast majority of history, the concept of a nation state did not exist. Today the nation state is so ubiquitous that many have come to internalize it as natural. This is not the case, and we should be especially wary of imposing our modern conceptions on a context where they would be nonsensical. For example, the impulse to imagine our ancestors as some closed-off, well-defined, unchanging homogeneous group having exclusive ownership over a territory that somehow corresponds to modern day borders has no basis in history. Unfortunately, this is the foundational myth of many reactionary ethno-nationalist ideologies.

As elsewhere, over the millennia kingdoms rose and fell, religions were founded, wars both holy and unholy were waged, and peoples lived, mixed, moved and died out. In other words, history happened.

This article does not aim to delve into the minutiae of this Palestinian history, indeed entire books could be -and have been- written on the subject. Rather the goal of this introduction is to describe the political context that lead up to the modern Palestinian question.

Following the decisive defeat of the Mamluks in the battle of Marj Dabiq (1516), the Levant laid open for the conquering Ottoman armies. A few months later they would enter Jerusalem and usher in one of the longest chapters of Palestinian history, lasting over 400 years.

Jerusalem held an important place in Ottoman eyes due to its religious and historic significance. From the onset of their rule, sweeping and majestic construction projects were carried out which would become staples of Jerusalemite architecture and topography, such as the striking walls of Jerusalem erected by Suleiman the magnificent.

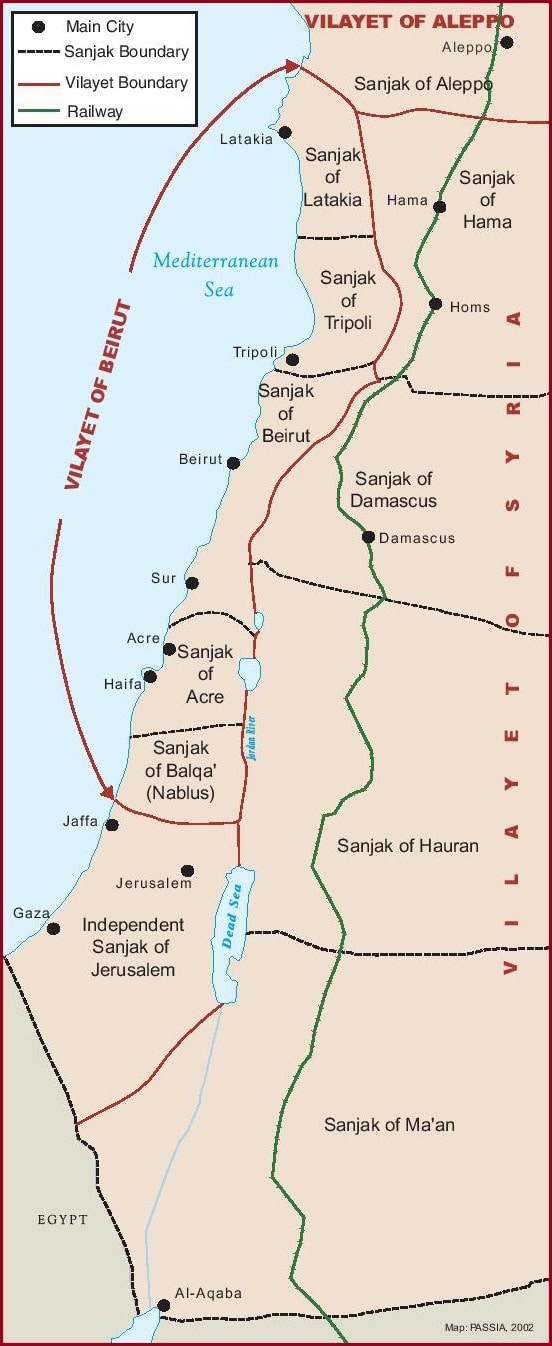

Over its history, the Ottomans divided Palestine into various political configurations and divisions. The last of which came in 1887, where Palestine was divided into 3 districts (Sanjaks): Jerusalem, Nablus and Acre. The Sanjak of Jerusalem was of such importance to the Ottomans that it would be governed directly by Constantinople (Later Istanbul).

The Ottoman Millet system and its various manifestations provided a certain degree of autonomy to minority religious and ethnic communities. While this system suffered from serious flaws, and its breadth and tolerance waxed and waned with different governors and social and economic circumstances, it was still superior to the outright persecution and pogroms which various religious groups on the European continent had to endure.

Relations between the numerous religious groups in Palestine were generally stable and peaceful, nurtured by more than a millennium of coexistence and shared adversity. For example, the inscription on the Jaffa Gate of Jerusalem reads “There is no God but Allah, and Abraham is his friend” in a nod to Christian and Jewish Ottomans, who like Muslims, are considered to be part of an Abrahamic religious tradition. Palestinian Muslims, perhaps uniquely so, were also in the habit of celebrating religious festivals in honor of the prophets and holy men of Judaism such as Reuben, son of Jacob. This attitude was also extended towards Christian Palestinians, where the keys of the Holy Sepulcher remain traditionally entrusted with a Muslim family to this day.

However, as with any empire, there were times of peace and prosperity, as well as times of hardship and war. Towards the end of the life of the Ottoman empire, the latter was much more common than the former. With the advent of European-style nationalism and the weakening of the Ottoman state, the relations between the various ethnic groups and communities would fray. There were rebellions against Ottoman rule, and Palestine even managed to win autonomy for a good while under the leadership of Daher al-‘Umar, however, it would eventually be crushed by Constantinople. These tensions would later be exacerbated by the Young Turk Revolution and the increasing efforts to Turkify the various Ottoman provinces.

The empire would eventually collapse after its defeat in the first World War, and the various peoples who made up its population -some of whom had sided with the Allies against the Ottomans- looked towards independence and establishing their own nation states. This of course, would be thwarted, as the peoples fell from the domination of one empire to the domination of many others.

It was during the final few decades of this dramatic collapse that a certain Austro-Hungarian thinker, Theodor Herzl, was planting the seeds of a new political movement that would change Palestinian history forever.

Convened in the Swiss city of Basel in 1897, the first Zionist congress included over 200 delegates from all over Europe. The program of the congress called for establishing a Jewish state in Palestine, and to begin coordinating the settlement of Zionists there. This, according to Herzl, the founder of political Zionism and president of the Zionist congress, would constitute a “solution for the Jewish question” and emancipate the Jewish people from persecution.

While there were other Zionist and proto-Zionist movements preceding this which had settled in Palestine, such as Hibbat Zion, the Zionist congress was the first to organize and marshal the colonization efforts in a centralized and effective way.

Zionism, then, is a settler-colonial political movement that calls for establishing a Jewish nation-state in Palestine with a Jewish majority. The issue here, of course, is that Palestine was already inhabited. The question of what to do with the native Palestinian Arabs animated much of the early discussions of the Zionist movement, though the consensus was that they needed to be removed somehow, either by agreement or by force. Indeed, there was no way to establish a Jewish majority state in Palestine without seriously displacing most of the native population.

When we call Zionism settler-colonialism, we refer to a very specific phenomenon. Settler colonialism differs from classic colonialism, in that settler colonialism only initially and temporarily relies on an empire for their existence. In many situations, the colonists aren’t even from the empire supporting them, and end up fighting the very sponsor that ensured their survival in the first place. Another difference is that settlers are not merely interested in the resources of these new lands, but also in the lands themselves, and to carve out a new homeland for themselves in the area.

Modern day Zionists might recoil at Zionism being called a colonial ideology, yet in the early days, the Zionist movement was astonishingly honest about its existence as a form of colonialism. For example, Herzl wrote in 1902 to infamous colonizer Cecil Rhodes, arguing that Britain recognized the importance of “colonial expansion”:

“You are being invited to help make history,” he wrote, “It doesn’t involve Africa, but a piece of Asia Minor ; not Englishmen, but Jews . How, then, do I happen to turn to you since this is an out-of-the-way matter for you? How indeed? Because it is something colonial.”

Vladimir Jabotinsky, in an essay titled The Iron Law (1925) stated that:

“A voluntary reconciliation with the Arabs is out of the question either now or in the future. If you wish to colonize a land in which people are already living, you must provide a garrison for the land, or find some rich man or benefactor who will provide a garrison on your behalf. Or else-or else, give up your colonization, for without an armed force which will render physically impossible any attempt to destroy or prevent this colonization, colonization is impossible, not difficult, not dangerous, but IMPOSSIBLE!… Zionism is a colonization adventure and therefore it stands or falls by the question of armed force. It is important… to speak Hebrew, but, unfortunately, it is even more important to be able to shoot – or else I am through with playing at colonizing.”

These quotations are merely the tip of the iceberg, but lest you think we are cherry-picking and choosing out of context passages, we invite you to read their original writings. There are only so many mental gymnastics you can perform to try and find a different meaning to “Zionism is a colonization adventure.”

To drive this point even further, the first Zionist bank established was named the ‘Jewish Colonial Trust’ and the whole endeavor was supported by the ‘Palestine Jewish Colonization Association’ and the ‘Jewish Agency Colonization Department’.

It would only be a matter of time before the Zionist movement began sending settlers to Palestine and forming a foothold with the goal of taking over the entirety of Palestine. The Ottoman defeat in WW1 and Palestine becoming a British mandate was the golden opportunity that would allow them to fulfill these aims. This will be discussed in depth in the next introductory article.

In the wake of its defeat in WW1, the Ottoman empire was dissolved and its regions carved up and divided among various European colonial powers. In the Levant, Palestine and Jordan fell under the mandate of the British, while Syria and Lebanon to that of the French. The British entered Jerusalem in 1917, and Palestine officially became a mandate in 1922.

Palestine was considered a ‘Class A’ mandate, meaning that it possessed sufficiently advanced infrastructure and administrative capabilities as to be considered provisionally independent, though it would still be under the control of the allied forces until it was deemed ready for full independence. This, of course, would never come to pass.

The mandate of Palestine provided a golden opportunity for the Zionist movement to achieve its aims. The British were far more responsive to Zionist goals than the Ottomans were, and had earlier produced the Balfour Declaration promising the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Despite the lofty words of Lord Balfour, a colonial empire massacring people all over the globe is not animated by altruism. The British had no genuine sympathy for the plight of the historically oppressed Jewish people; Rather, they saw in the Zionist movement a mechanism through which British interests in the Levant and Suez could be realized.

Emboldened by the Balfour Declaration and supportive British governors, the Zionist movement ramped up its colonization efforts and established a provisional proto-state within a state in Palestine, called the Yishuv. While the Yishuv’s relationship with the British had its ups and downs, the British provided the Zionists with explicit as well as tacit sponsorship which would allow them to thrive. Meanwhile, they would harshly repress any Palestinian movement or organization while turning a blind eye to Zionist expansion, which by the end of the mandate enabled the conquest and mass destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages and neighborhoods.

These are the circumstances and events which would ultimately culminate in the establishment of Israel through the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians and the erasure of their society. The next article will focus on Zionist aspirations, partition, the final years of the mandate of Palestine, the war of 1948, and the Nakba, the original sin of Israel’s genesis.